The Pen Proves Mightier than the Chicotte: 1st Battle

by Mac McKinney

Forward to the Past in the DR Congo, Part 4

For Part 1, LA Progressive Post: Le Roi-Souverain of the Congo Free State

For Part 2, LA Progressive Post: The Horror Begins: Forward to the Past in the D.R. Congo

For Part 3, LA Progressive Post: The Horror Crescendos

|

| George Washington Williams (source) |

It was George Washington Williams, a one-time Civil War soldier in the Union Army, who first loudly exposed what was going on in the Congo Free State to the outside world in a letter addressed to King Leopold, “An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo By Colonel, The Honorable Geo. W. Williams, of the United States of America,”. Williams had always been possessed with great energy, social consciousness and courage, enlisting in the Union Army at the age of 14, going on to fight with the Mexican Army in their rebellion against the French usurper, Emperor Maximilian, and then again in the American Indian Wars as a Buffalo Soldier, later becoming a minister, lawyer, Ohio state legislator, historian, writer and publisher.

In reality, Williams was not only an adventurer but a Renaissance Man with a unique religious bent. Once he was finally discharged from the Army as a wounded veteran, he enrolled in the then new, but now famed college for blacks, Howard University, but then soon moved on to the oldest graduate seminary in the country, Newton Theological Institution. Williams thus had the distinction of becoming the first African-American to graduate, in 1974, from Newton, becoming ordained as a Baptist Minister soon thereafter. He went on to hold several ministries, among them the historic Twelfth Baptist Church of Boston, of which he later wrote an 80 page history. Indeed Williams would develop a deep passion for writing, and was also extremely interested in journalism, soon approaching various progressive luminaries of his era with the persuasive proposition of starting up a news journal dedicated to African-Americans. Quoting from Wikipedia:

With support from many of the leaders of his time such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, Williams founded The Commoner, a monthly journal, in Washington, D.C. He was only able to publish eight issues. (source)

Perhaps stung by this noble effort ending in failure, Williams then moved to Cincinnati, Ohio to become the pastor of the Union Baptist Church. but he also began to study law, passing the bar, beginning his practice and, publicly ambitious, soon testing the stormy waters of politics. He would eventually become the first African-American elected to the Ohio State Legislature, although serving only one year, from 1880 to 1881. A bill he sponsored, ironically on the behalf of wealthy whites in a battle with local blacks over the Colored American Cemetery of Avondale infuriated some of the black community and cost him their support.

Amazingly, while all these endeavors were going on, he somehow found time to work on what became two pioneering and laudable works on African-American history. In 1883 the first book, A History of Negro Troops in the War of Rebellion and The History of the Negro Race in America 1619–1880, was published, the first in-depth and accurate history on African-Americans. His second one, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, "involved the gathering of oral histories from black Civil War veterans and the culling of newspaper accounts, both techniques which subsequently became basic resources in American historiography", to quote from Encyclopedia Brittanica (source).

Amazingly, while all these endeavors were going on, he somehow found time to work on what became two pioneering and laudable works on African-American history. In 1883 the first book, A History of Negro Troops in the War of Rebellion and The History of the Negro Race in America 1619–1880, was published, the first in-depth and accurate history on African-Americans. His second one, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, "involved the gathering of oral histories from black Civil War veterans and the culling of newspaper accounts, both techniques which subsequently became basic resources in American historiography", to quote from Encyclopedia Brittanica (source).

|

| A weathered copy of Williams' famous history (source) |

But it would almost seem that all of this background, education and experience were mere preparation for what was to come next, for now Williams' journalistic and historical inquisitiveness prompted him to take a world tour in the latter 1880s, during which sojourns he ended up, in 1889, interviewing King Leopold II in Belgium. This would be a fateful encounter.

Leopold, of course, extolled the glorious virtues of his new stewardship of the Congo Free State to Williams, whose interest was perked enough that he took it upon himself to visit this Congolese paradise, which, ironically, Leopold ended up objecting to, even personally attempting to dissuade him after learning, through his agents, of the planned trip. And Williams may very well have also seen some of the articles beginning to leak out in London and elsewhere about Belgian-led atrocities in what was officially being depicted everywhere as a blossoming monument to Christian civilizing influences. This would have aroused his curiosity and concerns even more. Be that as it may, Samuel S. McClure, the famous Irish-American muckraker, had, coincidentally or not according to one biography of Williams, commissioned him to write articles on the treatment of the natives under Belgian rule (source).

William would not be dissuaded by Leopold and made good his word, dauntlessly trekking into the Congo in 1890, which dramatic adventure author Adam Hochschild briefly describes in his classic book, King Leopold's Ghost:

Almost the only early visitor to interview Africans about their experience of the regime, he took extensive notes, and, a thousand miles up the Congo River, wrote one of the greatest documents in human rights literature, an open letter to King Leopold that is one of the important landmarks in human rights literature. Published in many American and European newspapers, it was the first comprehensive, detailed indictment of the regime and its slave labor system. Sadly, Williams, only forty-one years old, died of tuberculosis [and pleurisy - Mac] on his way home from Africa, but not before writing several additional denunciations of what he had seen in the Congo. In one of them, a letter to the U.S. Secretary of State, he used a phrase that was not commonly heard again until the Nuremberg trials more than fifty years later. Leopold II, Williams declared, was guilty of "crimes against humanity." (source)

Williams himself described his tortuous journey, which negatively impacted his health, in the famous open letter he later wrote to President Harrison:

Williams, outraged by what he saw and heard over these months, wrote his famous open letter to Leopold from Stanley Falls, Central Africa on July 18, 1890. Leaving nothing to chance in exposing his findings to the American government, he followed that up with an open letter to American President Benjamin Harrison from the province of St. Paul de Loanda, Portuguese Angola on October 14, 1890 entitled:

My travels extended from the mouth of the Congo atBanana, where it empties into the South Atlantic, to itsheadwaters at the Seventh Cataract, at Stanley-Falls; and from Brazzaville, on Stanley-Pool, to the South Atlantic Ocean at Loango, I passed through the French-Congo, via Comba, Bouenza and Loudima. In four months, or in one hundred and twenty five days I traveled 3,266 miles, passing from Southwestern Africa to East Central Africa, and back to the sea. I camped in the bushes seventy-six times, and on other occasions received hospitality of traders, missionaries and natives. Of my eighty-five natives I lost not a life, although we sometimes suffered from fatigue, hunger and heat. (source)

|

| Williams studied, among others, the fierce Bangala tribe, as represented by this warrior and his family (1889) - Credit: Alexandre Delcommune (source) |

Williams, outraged by what he saw and heard over these months, wrote his famous open letter to Leopold from Stanley Falls, Central Africa on July 18, 1890. Leaving nothing to chance in exposing his findings to the American government, he followed that up with an open letter to American President Benjamin Harrison from the province of St. Paul de Loanda, Portuguese Angola on October 14, 1890 entitled:

FIFTH—Your Majesty’s Government is excessively cruel to its prisoners, condemning them, for the slightest offences, to the chain gang, the like of which can not be seen in any other Government in the civilized or uncivilized world. Often these ox-chains eat into the necks of the prisoners and produce sores about which the flies circle, aggravating the running wound; so the prisoner is constantly worried. These poor creatures are frequently beaten with a dried piece of hippopotamus skin, called a “chicote”, and usually the blood flows at every stroke when well laid on. But the cruelties visited upon soldiers and workmen are not to be compared with the sufferings of the poor natives who, upon the slightest pretext, are thrust into the wretched prisons here in the Upper River. I cannot deal with the dimensions of these prisons in this letter, but will do so in my report to my Government.

SIXTH.—Women are imported into your Majesty’s Government for immoral purposes. They are introduced by two methods, viz., black men are dispatched to the Portuguese coast where they engage these women as mistresses of white men, who pay to the procurer a monthly sum. The other method is by capturing native women and condemning them to seven years’ servitude for some imaginary crime against the State with which the villages of these women are charged. The State then hires these woman out to the highest bidder, the officers having the first choice and then the men. Whenever children are born of such relations, the State maintains that the women being its property the child belongs to it also. Not long ago a Belgian trader had a child by a slave-woman of the State, and he tried to secure possession of it that he might educate it, but the Chief of the Station where he resided, refused to be moved by his entreaties. At length he appealed to the Governor-General, and he gave him the woman and thus the trader obtained the child also. This was, however, an unusual case of generosity and clemency; and there is only one post that I know of where there is not to be found children of the civil and military officers of your Majesty’s Government abandoned to degradation; white men bringing their own flesh and blood under the lash of a most cruel master, the State of Congo.

Williams' letter ends with this searing indictment of the Government of the Congo Free State, and, more indirectly, of Leopold himself:

CONCLUSIONS

Against the deceit, fraud, robberies, arson, murder, slave-raiding, and general policy of cruelty of your Majesty’s Government to the natives, stands their record of unexampled patience, long-suffering and forgiving spirit, which put the boasted civilisation and professed religion of your Majesty’s Government to the blush. During thirteen years only one white man has lost his life by the hands of the natives, and only two white men have been killed in the Congo. Major Barttelot was shot by a Zanzibar soldier, and the captain of a Belgian trading-boat was the victim of his own rash and unjust treatment of a native chief.

All the crimes perpetrated in the Congo have been done in your name, and you must answer at the bar of Public Sentiment for the misgovernment of a people, whose lives and fortunes were entrusted to you by the august Conference of Berlin, 1884—1 885. I now appeal to the Powers which committed this infant State to your Majesty’s charge, and to the great States which gave it international being; and whose majestic law you have scorned and trampled upon, to call and create an International Commission to investigate the charges herein preferred in the name of Humanity, Commerce, Constitutional Government and Christian Civilisation.

I base this appeal upon the terms of Article 36 of Chapter VII of the General Act of the Conference of Berlin, in which that august assembly of Sovereign States reserved to themselves the right “to introduce into it later and by common accord the modifications or ameliorations, the utility of which may be demonstrated experience”.

I appeal to the Belgian people and to their Constitutional Government, so proud of its traditions, replete with the song and story of its champions of human liberty, and so jealous of its present position in the sisterhood of European States—to cleanse itself from the imputation of the crimes with which your Majesty’s personal State of Congo is polluted.

I appeal to Anti-Slavery Societies in all parts of Christendom, to Philanthropists, Christians, Statesmen, and to the great mass of people everywhere, to call upon the Governments of Europe, to hasten the close of the tragedy your Majesty’s unlimited Monarchy is enacting in the Congo.

I appeal to our Heavenly Father, whose service is perfect love, in witness of the purity of my motives and the integrity of my aims; and to history and mankind I appeal for the demonstration and vindication of the truthfulness of the charge I have herein briefly outlined. And all this upon the word of honour of a gentleman, I subscribe myself your Majesty’s humble and obedient servant,

GEO. W. WILLIAM

Stanley Falls, Central Africa,

July 18th, 1890. (source)

You can also actually read a photocopy of the original second letter to President Harrison that I quoted earlier, and even listen to an audio presentation of it at THIS WEBSITE. These are the closing sentences of this second letter:

The people of the United States of America have a just right to know the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, respecting the Independant State of Congo, an absolute monarchy, an oppressive and cruel Government, an exclusive Belgian colony, now tottering to its fall. I indulge the hope that when a new Government shall rise upon the ruins of the old, it will be simple, not complicated; local, not European; international, not national; just, not cruel; and, casting its shield alike over black and white, trader and missionary, endure for centuries. (source)

Since international mail was quite slow in the latter 19th Century, being dependent on steam ships, by the time President Harrison received the report addressed to him, copies of this second letter had already appeared in European and American newspapers and given King Leopold's minions time to formulate a typically vile media counterattack, character assassination. Thus when the New York Times ran a front-page piece on Williams' allegations on April 14, 1891, they struck back the very next day, to quote from Wikipedia:

Leopold’s supporters in America submitted an article that accused Williams of living a lie and committing adultery. The headline read “HE PROSPERED FOR A TIME, BUT HIS TRUE CHARACTER WAS LEARNED.”[8] During the late summer of 1891 the Belgian Parliament defended Leopold and gave a forty-five page report to the press circuit, effectively refuting Williams' accusations. Williams died on August 2 with his reputation tarnished. (source)

Williams' valiant expose of the Free Congo State had cost him dearly, his health badly damaged by his taxing travels in the Congo, his reputation soiled by the Machiavellians rife in Leopold's global power network, but he had landed some blows and sown the seeds of doubt and skepticism in Western minds about Leopold's ivory tower of colonial virtue.

This had really been the first battle in what would evolve into a relentless and global propaganda war, and Williams was really the first martyr in the Good Cause of wrestling the Congo from Leopold's "talons" through the power of the pen. But another journalist-in-the making was being groomed, although he didn't even know it yet, by destiny to pick up the torch of truth and justice that the dying Williams had released from his grip, and that man was Edmund Dene Morel.

This had really been the first battle in what would evolve into a relentless and global propaganda war, and Williams was really the first martyr in the Good Cause of wrestling the Congo from Leopold's "talons" through the power of the pen. But another journalist-in-the making was being groomed, although he didn't even know it yet, by destiny to pick up the torch of truth and justice that the dying Williams had released from his grip, and that man was Edmund Dene Morel.

|

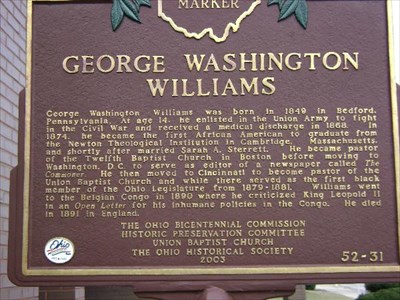

| Historical marker of George Washington Williams in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio (source) |

*********

Next time,

Part Five: The Pen Proves Mightier than the Chicotte: Full Scale War

No comments:

Post a Comment

Feel free to comment but keep it civil or your comment will be exiled to the voids of cyberspace.