|

| (source) |

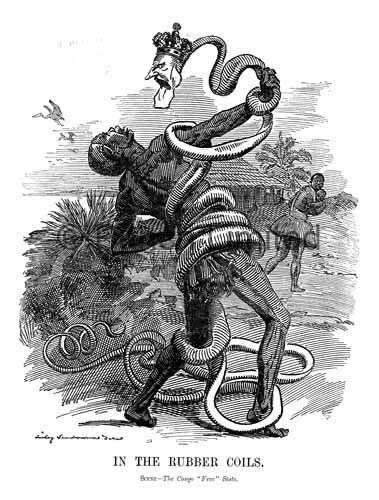

The Horror Crescendos

by Mac McKinney

Forward to the Past in the D.R. Congo, Part Three

It was Joseph Conrad, the great Polish-born and naturalized English author and sea-faring adventurer who had made his own sojourn into the Congo Free State in 1889, who first penned Marlon Brando’s Apocalypse Now-iconic phrase, “The horror! The horror!” in his famous novella, The Heart of Darkness, that mirrored his own wrenching experiences in the Congo. Having himself served on a river-steamboat traveling into the interior, he met individuals, witnessed abominations and heard stories that left him afflicted in soul and body by the time he left. His novella describes how even the most well-intentioned of European minds, as encapsulated in the figure of the ivory agent Mr. Kurtz, could sink into the depths of depravity, insanity and evil, once confronted with the primordial immensity of the interior and no moral restraints.

Horror is a recurring theme in the history of the modern Congo since its inception as a colonial state through today, a curse that has ebbed and flowed over the years like a demonic, blood-red river that suddenly disappears underground only to reemerge years later in ghastly obscenity, as witness the millions slain, maimed, raped and traumatized in just the last decade alone in today’s DR Congo. How to end this carnage is one of the great challenges of our times.

One notes how, in this metaphoric blood-river’s first surge in the 1880s, scores of restless, often unsavory Europeans and other adventurers with appetites for quick wealth stumbled into the Congo in response to the colonial call to “civilize” and develop this unknown territory, yet learned quickly enough that this usually meant signing onto a trade company or government post whose major pursuit was competing in the rapacious race to extract as much ivory as possible from the Congo. And these men found that the pressure was enormous, from King Leopold on down to the lowliest manager, to obtain this ivory at whatever cost and that they, reinforced by a sense of cultural superiority easily transformable into outright racism, could bend and ignore normal moral restraints when dealing with their beasts of burden, the Congolese natives, to achieve this.

But it was the sheer enthusiasm and “extreme prejudice”, another term from the movie, Apocalypse Now, with which many of these men took to their cruelties time and time again throughout the history of the Congo Free State that is so disturbing, enthusiasm for continuously extending the boundaries of moral offense and outrage that eventually would devolve into deadly banality as each new cruelty became systematic and routine. Conrad depicts this atmosphere in Heart of Darkness, when his protagonist, Marlow, describes coming across some wretches who had been worked to the point of death and abandoned, as if they were expendable pack animals no longer of any use:

Black shapes crouched, lay, sat between the trees leaning against the trunks, clinging to the earth, half coming out, half effaced within the dim light, in all the attitudes of pain, abandonment and despair……..They were dying slowly – it was very clear. They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now, – nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confused in the greenish gloom. Brought from all the recesses of the coast in all the legality of time contracts, lost in uncongenial surroundings, fed on unfamiliar food, they sickened, became inefficient, and then were allowed to crawl away and rest…. (from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad).

But these first rumblings of King Leopold’s infernal machine were nothing as compared with what was to come next, for despite all of his and his colonial administration’s frenzied efforts to boost production, the profits from the ivory trade alone could not keep pace with the costs of running the Congo Free State. Leopold, growing more and more desperate as the debts piled up, would have to find another way to secure his fortune.

That way was soon illumined through, ironically, the innocent creation, circa 1888, of the first practical inflatable bicycle tire by the Scottish inventor, John Boyd Dunlop, a giant step toward industrializing transportation, first with bicycles, soon after with automobiles. Dunlop himself began to manufacture tires in earnest by 1890, though he was merely the point man for the army of entrepreneurs that would follow.

Sales took off quickly, producing a huge demand, almost overnight, for raw rubber, a fact not lost on King Leopold, always the astute businessman, who realized that here was a golden opportunity and that he must seize the moment dramatically, for wild rubber vines proliferated throughout the Congo. All of his egomaniac royal dreams suddenly hinged on harvesting these vines and getting them to market in maximum quantity with maximum speed and efficiency, before global competition could begin to eat into his potential profits.

So orders went out to establish rubber companies in the Congo Free State, dole out territorial concessions and facilitate the creation of a massive work force, one far greater in size than the one gang-pressed into the ivory trade, to harvest and transport the tapped rubber sap or latex, grueling and exhausting work that Congolese natives had little inclination for naturally. So once again Leopold gave the lie to his pretensions of civilizing and uplifting the Congolese people, for now he was about to submerge his millions of “subjects” into a Hellish corvée system, to use the fitting Feudal term for forced labor, but on an almost unprecedented scale with unprecedented cruelties designed to drive the Congolese to produce rubber relentlessly. Indeed this period of corvée in the so-called Free State would last several decades and come to be known as the “Rubber Terror”.

The history of just one such incorporated rubber concern, the Abir Congo Company, sheds much light into the nature of this entire sordid enterprise. Abir was initially called the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company or ABIR (all the English later dropped out), founded with quickly enticed English and Belgian investments and just as quickly granted a handsome concession in the northern Congo. Critically, the colonial administration awarded the company the right to tax all the inhabitants in what can only be considered a ruse to begin implementing forced labor, because the tax was to be paid as rubber collected from rainforests. Quoting from Wikipedia:

The collection system revolved around a series of trade posts along the two main rivers in the concession. Each post was commanded by a European agent and manned with armed sentries to enforce taxation and punish any rebels.

Abir enjoyed a boom through the late 1890s, by selling a kilogram of rubber in Europe for up to 10 fr which had cost them just 1.35 fr to collect and transport. However, this came at a cost to the human rights of those who couldn't pay the tax with imprisonment, flogging and other corporal punishment recorded. Abir's failure to suppress destructive harvesting methods and to maintain rubber plantations meant that the vines became increasingly scarce and by 1904 profits began to fall. During the early 1900s famine and disease spread across the concession, a natural disaster judged by some to have been exacerbated by Abir's operations, further hindering rubber collection. The 1900s also saw widespread rebellions against Abir's rule in the concession and attempts at mass migration to the French Congo or southwards. These events typically resulted in Abir dispatching an armed force to restore order. (source)

“Armed sentries” and “armed force” more often than not meant units of Leopold’s Force Publique, but could also mean ex-slaves (de facto or otherwise) or callous self-serving local villagers, or even black mercenaries, all eager to be elevated to the status of “policemen” and quota enforcers, armed with rifles and chicottes by the rubber companies and sent out against recalcitrant villagers to discipline and punish them, all this analogous, somewhat, to the American Slave South’s system of enforcement through plantation overseers, black and white, and local armed posses and bounty hunters, except for one critical difference. In the American South, plantation owners had to pay often high prices for their slaves, and were subsequently not terribly interested in the massive and wanton maiming and slaughter of their human “commodities”. In the Congo, there were no such chattel investments to protect, only scarcely valued victims by the tens and hundreds of thousands to be gang-pressed into service and brutalized into submission, or worse still, into oblivion. Thus to the accountants of King Leopold, this entire sordid operation was a magnificent (in the short term at least) financial conquest.

|

| Force Publique soldiers guarding forced laborers, slaves by any other name (source) |

Ironically, since we are speaking of cost and overhead, the colonial administrators had enacted the law that villagers must be paid for their rubber, in actuality both a sop to appease European consciences and a fig leaf to mask the grand exploitation underway, because payment was of the sort that Columbus or the Conquistadors had made to the natives of the Western Hemisphere, shiny beads, cheap knives and other bulk barter goods, the better to enslave them with.

I have already referenced Joseph Conrad’s fictionalized account, in Heart of Darkness, of the misery engendered by the exploitation of trade resources in the Congo, and how his anti-hero, the agent Kurtz, exemplified the descent of Europeans into moral depravity there. But the great problem was that there was not merely an occasional “Kurtz” run amok, but that there were many “Kurtz’s” running amok, often in high places, throughout the zones, sectors and posts of the Congo Free State.

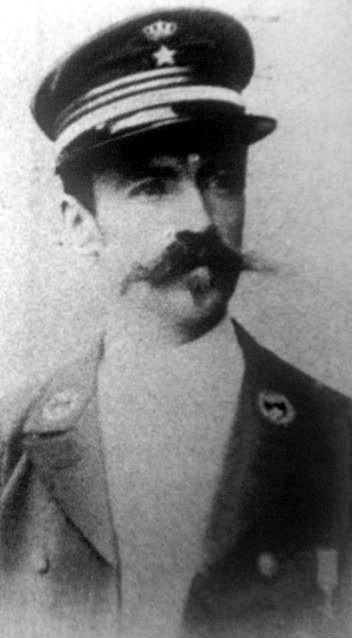

The author of King Leopold's Ghost, Adam Hochschild, actually thought that the prototype for Kurtz might have been a Belgian named Leon Rom, a poorly educated lad who joined the Belgian army at 16 and nine years later, in 1886, “found himself in the Congo in search of adventure. He became district commissioner at Matadi and was later put in charge of the African troops in Leopold's murderous Force Publique army in the Congo.

Rom's brutality knew no bounds. It was such that even the white people working with him were shocked to their boots.

"When Rom was station chief at Stanley Falls," Hochshild reveals, "the governor general sent a report back to Brussels about some agents who 'have the reputation of having killed masses of people for petty reasons'. He mentions Rom's notorious flower bed rigged with human heads, and then adds: 'He kept a gallows permanently erected in front of the station'." (source)

|

| Leon Rom (source) |

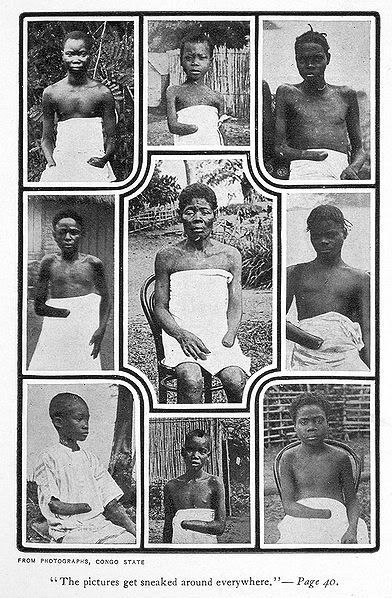

As the corvée system extended itself like a black plague, resistance naturally increased, many Congolese fleeing into the rainforests or across borders, some fighting back, some even sabotaging the wild rubber vines in their areas to hasten the hated rubber’s demise. To meet the growing challenges to their ever-increasing rubber quotas and rapacious oppression, agents, officers and government officials simply increased their cruelties in the form of punitive raids on villages, often resulting in wholesale slaughters to set examples for the other villages, endless whippings and beatings, and worse still, the widespread practice of mutilations, engendered, ostensibly, to save bullets.

To prevent the waste of ammunition, soldiers of the Force Publique were actually ordered to bring back the right hand of every man they shot to prove they had used their cartridges frugally, but this of course could easily be abused if one, say, shot a wild monkey and then conveniently chopped off the right hand of the next villager he came upon. Mutilations also simply served as punishment for not meeting the often egregious rubber quotas, or “taxes”, a practice that can be traced all the way back to, if not beyond, Christopher Columbus colonizing the Caribbean island of Hisponolia, where he would have the hands cut off of the indigenous Arawaks (or Tainos) who failed to meet his heavy gold or cotton quotas.

But let us return to a more detailed example of how yet another “Kurtz”, District Commissioner Leon Fievez, enforced the Rubber Terror in the Congo, again quoting from King Leopold's Ghost:

As the rubber terror spread throughout the rain forest, it branded people with memories that remained raw for the rest of their lives. A Catholic priest who recorded oral histories half a century later quotes a man, Tswambe, speaking of a particularly hated state official named Leon Fievez, who terrorized a district along the river three hundred miles north of Stanley Pool: All the blacks saw this man as the Devil of the Equator...From all the bodies killed in the field, you had to cut off the hands. He wanted to see the number of hands cut off by each soldier, who had to bring them in baskets...A village which refused to provide rubber would be completely swept clean. As a young man, I saw [Fievez's] soldier Molili, then guarding the village of Boyeka, take a big net, put ten arrested natives in it, attach big stones to the net, and make it tumble into the river...Rubber caused these torments; that's why we no longer want to hear its name spoken. Soldiers made young men kill or rape their own mothers and sisters. A Force Publique officer who passed through Fievez's post in 1894 quotes Fievez himself describing what he did when the surrounding villages failed to supply his troops with the fish and manioc he had demanded: "I made war against them. One example was enough: a hundred heads cut off, and there have been plenty of supplies at the station ever since. My goal is ultimately humanitarian. I killed a hundred people...but that allowed five hundred others to live."

(source)

This was the statement of a totally self-deluding Machiavellian, who posited that such sordid means can justify “noble” ends without even mentioning that the entire rubber enterprise was a massive crime against the Congolese in the first place. That fact, we can imagine, Fievez repressed from his conscience completely. And accounts have it that the self-described "humanitarian" Fievez, before his personal reign of terror was over, “killed roughly 1,300 Congolese, burned down 162 villages, cut down plantations and destroyed vegetable gardens - leading indirectly to countless additional deaths through malnutrition and starvation.” (source)

|

| Victims of the Rubber Terror (source) |

But we have not seen all of the company agents’ and state officials’ methods of coercion yet. Another cynical, ever-metastasizing tactic was kidnapping, to again quote from Wikipedia on the ABIR (later Abir) Company:

Yet the main incentive for villagers to bring rubber was not the small payments but the fear of punishment. If a man did not fulfill his quota his family may have been taken hostage by ABIR and released only when the quota was filled. The man himself was not imprisoned as that would prevent him from collecting rubber.[14] Later agents would simply imprison the chief of any village which fell behind its quota, in July 1902 one post recorded that it held 44 chiefs in prison. These prisons were in a poor condition and the posts at Bongandanga and Mompono recorded death rates of three to ten prisoners per day each in 1899.[14] Those with records of resisting the company were deported to forced labour camps. There were at least three of these camps, one at Lireko, one on the Upper Maringa River and one on the Upper Lopori River.[14] In addition to imprisonment corporal punishment was also used against tax resisters with floggings of up to 200 lashes with a chicotte…” (source)

But it was not only chiefs who were kidnapped for extortion purposes, but the wives of the village men as well. Again to quote Hochschild:

Another popular tactic was more sophisticated in its gendering. When men fled into the jungle, women and others in the community would be held hostage until they returned to face conscription and probable death. Many thousands of these women were eventually transported into a version of corvée themselves; a Swedish missionary described seeing "a group of seven hundred women chained together and transported," on their way to probable rape and prostitution -- in any case to brutalization and servitude -- on the coast. Similar strategies were employed to secure supplies of wild rubber for export, before the establishing of the plantation economy. A British vice consul described one Congo officer's practice as being "to arrive in canoes at a village, the inhabitants of which invariably bolted on their arrival; ... [his forces] attacked the natives until able to seize their women; these women were kept as hostages until the Chief of the district brought in the required number of kilogrammes of rubber. The rubber having been brought, the women were sold back to their owners for a couple of goats apiece, and so he continued from village to village until the requisite amount of rubber had been collected. ... If you were a male villager, resisting the order to gather rubber could mean death for your wife. She might die anyway, for in the stockades food was scarce and conditions were harsh. (Hochschild, King Leopold's Ghost, pp. 126, 130, 161-62). (source)

Needless to say, many of these imprisoned wives were raped and abused by their guards, as documented by missionaries and others during the Rubber Terror. Thus sexual humiliation was heaped upon trauma, mutilation, exploitation, sickness, endless death and vast injustice against the natives of the Congo Free State, the Terror only declining when three things happened: 1) the population became so decimated, by the millions in just two decades, that the corvée system was becoming counterproductive and unprofitable; 2) the ongoing, destructive rubber harvesting methods had badly depleted the rubber vine reserves by the early 1900s, and 3) as word leaked out about the garish realities inside the Congo, growing outrage led to the creation of an international human rights movement to confront King Leopold’s odious tenure of his Chamber of Horrors domain.

********

Next time,

Part Four: The Pen Proves Mightier than the Chicotte

Well done. Noticing that the Congo is in the news again and has been receiving a lot of attention re: Joseph Kony. This recent documentary is a devastating indictment of Leopold II and Belgium and is good adjunct material to this essay. Also, the US Military has 100 advisers in Uganda ostensibly to train the Ugandan Army for use in bring Joseph Kony out of the jungles and before a court. I think what we're seeing is colonization under a softer master. Yeah, right. I was stunned to learn that the cutting off of hands originated in Belgium and that children in the army was a Leopold/Belgium/commissioner embedded idea.

ReplyDeleteVideo:

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-4748355130635434378&hl=sv

Thanks tokyowashi,

DeleteI've seen the Red Rubber video, yes, an excellent expose!

Kony is extremely hard to capture, expert at disappearing into the bush. Watch this video to see what I mean: http://plutonianmac.blogspot.com/2012/03/manhunt-catching-kony-uganda-october.html. What US troops bring to the hunt is advanced technological capabilities and training. I do not know if they have actually joined in the hunt or are just training Ugandan forces. They would have to get permission from the other governments where Kony has been sighted to trek into the DR Congo, Central African Republic and Southern Sudan. I wouldn't worry about American motives. The Obama Admin pretty much had to be dragged kicking and screaming by a Congressional bill and NGOs demanding help to dispatch these troops in the first place.